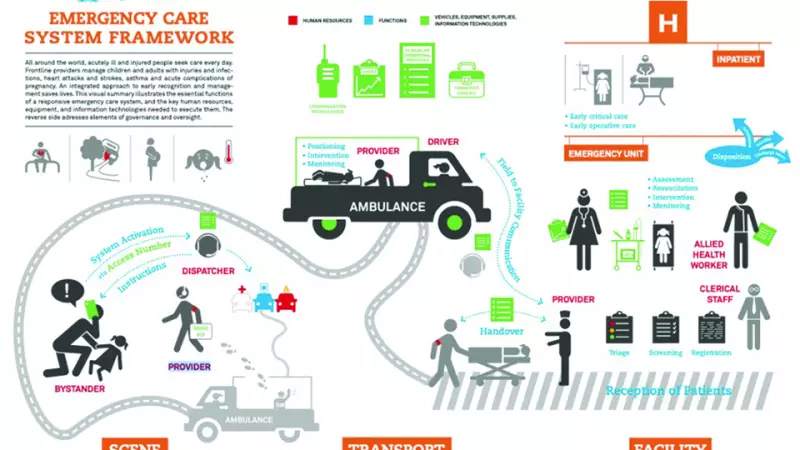

In any modern society, accidents are inevitable. Yet, the severity of resulting injuries and deaths is highly manageable with prompt, coordinated emergency care. In Nigeria, the stark opposite is the daily reality. The routine absence of functional emergency medical services, uninformed first responders, inactive helplines, and ill-equipped hospitals are systematically destroying the lifesaving 'Golden Hour' rule, leading to countless preventable fatalities.

Tragic Cases Highlight Systemic Failure

The human cost of this failure is devastating and widespread. Mrs Charity Unachukwu died on September 20, 2025, at the University of Nsukka Teaching Hospital (UNTH) following a vehicle accident. Her sister, Phina Ezeagwu, alleged that over 12 hours of delay before treatment commenced cost Unachukwu her life. While the hospital disputed some claims, it acknowledged critical communication and coordination gaps.

This was not an isolated incident. Adetunji 'Teejay' Opayele, co-founder of retail startup Bumpa, died on March 5, 2025, in Lagos after being knocked down. Bystanders faced refusals from multiple hospitals before he could get help. Similarly, Greatness Olorunfemi, a 'one-chance' robbery victim, died in September last year before reaching Maitama Hospital after being attacked on the Katampe-Kubwa road.

A contrasting story of what is possible emerged on New Year's Day. A quick response from TRACE, Police, and FRSC operatives within the Golden Hour saved lives after a ghastly accident on the Lagos-Ibadan Expressway that killed eight, including two toddlers. This occurred just days after boxing icon Anthony Joshua and his friends survived a crash on the same expressway, an event that drew international scrutiny to Nigeria's emergency response flaws.

The Crumbling Infrastructure of Care

The 'Golden Hour' refers to the critical first 60 minutes after a major trauma, where timely intervention drastically increases survival odds. The Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC) reported that over 3,400 people died in road crashes between January and September 2025, with 22,162 injured. Experts argue these numbers would be far lower with a functional emergency system.

A Guardian investigation visiting hospitals in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) found an overwhelmed system. Facilities like the Federal Medical Centre Jabi, Maitama Hospital, and Asokoro District Hospital grapple with severe manpower shortages, burnout, and poor infrastructure. At the National Hospital, limited bed space forced some emergency patients to be attended to in a pharmacy triage area, raising safety concerns.

The situation is mirrored nationwide. While the Alex-Ekwueme Federal University Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, is now one of only 10 accredited emergency medicine training centres, many regions, like the South-East, lack dedicated trauma centres. A study in the Journal of Public Health and Emergency found only 21% of Nigerians involved in road crashes used emergency services, with an average 30-minute response time.

National Helplines and Systemic Roadblocks

In 2022, the government launched the National Emergency Medical Services and Ambulance System (NEMSAS) to bridge these gaps. However, after three years, its operations remain suboptimal due to low awareness, poor communication networks, a lack of equipped ambulances, and under-capacitated staff.

Access is meant to be through the toll-free national emergency number 112. Dr. Emuren Doubra, NEMSAS National Programme Manager, confirmed the number covers about 24 states but is only fully functional in some, plagued by connectivity issues and administrative challenges. A senior Lagos State Emergency Management Authority (LASEMA) official noted Lagos operates two numbers, 112 and 767, due to its early adoption of an emergency system.

Yet, public ignorance is rife. Safety expert Adenusi Patrick stated that if you ask 100 Nigerians about the emergency number, 99 would not know it. This lack of awareness, coupled with motorists' refusal to yield to ambulances and chronic traffic congestion, cripples response efforts.

Calls for Training, Funding, and Motivated Workforce

Stakeholders are unanimous: multi-sectoral failures hold the system hostage. Dr. Kwarshak Kevin Yakubu, Second Vice President of the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors (NARD), emphasized the critical shortage of doctors, with a ratio of one to over 1,900 patients. He stressed that motivating healthcare workers is as crucial as providing equipment.

Safety advocates like Bolanle Edwards of the Strap and Safe Child Foundation and retired safety director Adeyinka Adebiyi called for continuous training and retraining of emergency personnel. They highlight the unprofessional interventions often seen at accident scenes, which can exacerbate injuries.

While Lagos State has introduced innovations like ambulance bikes to navigate traffic and is refurbishing vandalized ambulance points, these are localized solutions. The national picture remains dire. Until the government thoroughly addresses the intertwined challenges of funding, infrastructure, workforce motivation, and public awareness, Nigeria will continue to record needless losses, one ruined Golden Hour at a time.