The recent United States-led invasion of Venezuela and the subsequent extradition of its President, Nicolas Maduro, to face narco-terrorism charges have sent shockwaves far beyond Latin America. In Nigeria, analysts and commentators are sounding the alarm, drawing uncomfortable parallels between the two nations and questioning the path Nigeria is on. The core fear is that Nigeria's persistent governance failures and economic mismanagement could invite similar external intervention, eroding the country's hard-won sovereignty.

Parallel Paths: From Resource Wealth to National Ruin

Venezuela and Nigeria, both blessed with enormous oil wealth, are now textbook cases of the 'resource curse.' Venezuela sits on the world's largest proven oil reserves, yet its economy has catastrophically collapsed. Its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) plummeted by 80% in a decade, with inflation hitting 150% in 2025 and over 90% of its population living in poverty.

Nigeria's story echoes this tragic narrative. With approximately 37 billion barrels of proven oil reserves and 209 trillion cubic feet of gas, the country has exported crude for over 50 years. However, since the mid-1980s, the economy has stagnated. A recent PwC forecast projects Nigeria's poverty rate could rise to 62%, pushing about 141 million citizens below the poverty line. While official inflation figures may fluctuate, the reality for households is brutal: the cost of cooking gas often surpasses that of the food itself, and essentials like medicine and transport have become prohibitively expensive.

The fundamental similarity is a prolonged absence of accountable leadership. In both nations, a corrupt political class has siphoned resource wealth, leaving citizens impoverished and infrastructure crumbling. Venezuela now produces barely one million barrels of oil per day, while Nigeria struggles to reach two million due to theft and operational incapacity.

Sovereignty Under Siege: The Spectre of External Intervention

The situation has moved from economic analysis to tangible security threats. The Christmas Day U.S. airstrikes on terrorist facilities in Sokoto State marked a dramatic escalation. While the Nigerian government called it a collaborative effort, it raised profound questions about the abdication of sovereign duty.

Civil society groups have accused President Bola Tinubu of ceding constitutional authority by 'inviting a foreign government to manage what is fundamentally an internal security challenge.' Their concern is that the Sokoto strikes may be a prelude to deeper involvement, especially as terrorist attacks continue despite heightened military operations. Former U.S. President Donald Trump's warning that additional strikes could follow if attacks persist adds to this anxiety.

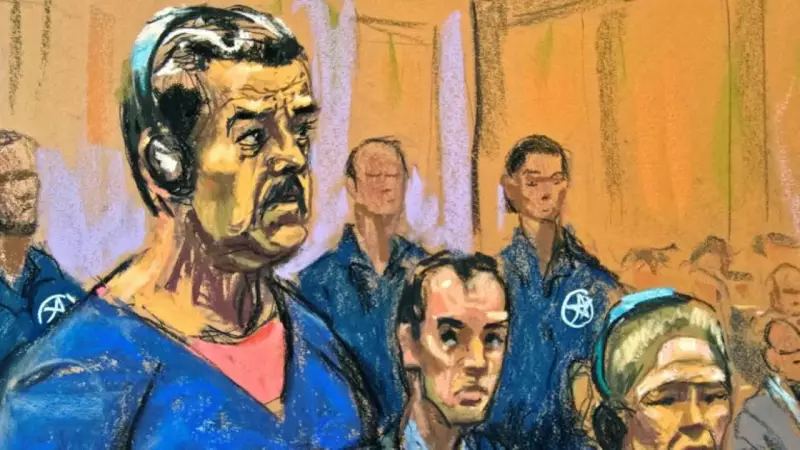

The Venezuela template is ominous. After the invasion, the interim leadership under Delcy Rodriguez quickly agreed to cooperate with the U.S., effectively ceding self-rule. Trump has since called off further strikes in Caracas, acknowledging the government's compliance as a 'smart gesture.' The worry for Nigerian patriots is that a nation once assertive in regional and global affairs is now perceived as vulnerable, with a political class some of whom have 'despicable dossiers locked in FBI files.'

Internal Decay Fuels External Vulnerability

The external pressures are compounded by relentless internal political crises. The moment President Tinubu departed for a New Year holiday, the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory, Nyesom Wike, relocated to Port Harcourt, initiating early 2027 campaign activities for Tinubu and instigating fresh impeachment proceedings against Governor Siminalayi Fubara. This blatant political rascality, potentially contravening electoral laws, exemplifies the governance distractions that prevent a unified front against national threats.

Furthermore, institutions meant to uphold accountability are viewed with deep suspicion. The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) faces accusations of being weaponised against opposition figures. The case of former Kogi State Governor Yahaya Bello, who evaded arrest, is cited as an example of perceived selective justice. The call is for transparent, expeditious, and impartial prosecution to restore public trust.

Even the electoral body, INEC, faces scrutiny. Its decision to finally delist Julius Abure as Labour Party chairman only after Peter Obi joined the African Democratic Congress (ADC) raises questions about its timing and impartiality.

The ultimate symptom of state failure is the mass exodus of citizens. Since 2014, about eight million Venezuelans have fled their country. Similarly, millions of Nigerians are exploring every avenue to escape hardship—through official visas or deadly journeys across the Sahara and Mediterranean. This desperate brain and brawn drain cripples the nation's future.

In conclusion, the Venezuela scenario is not a distant fantasy for Nigeria but a plausible cautionary tale. The combination of economic collapse, security failure, political corruption, and institutional weakness creates a perfect storm that threatens national sovereignty. The path away from 'the Venezuela treatment' requires a urgent, sincere, and collective commitment to accountable leadership, economic diversification, and the unwavering defense of Nigeria's constitutional order from within. The time for corrective action is swiftly running out.